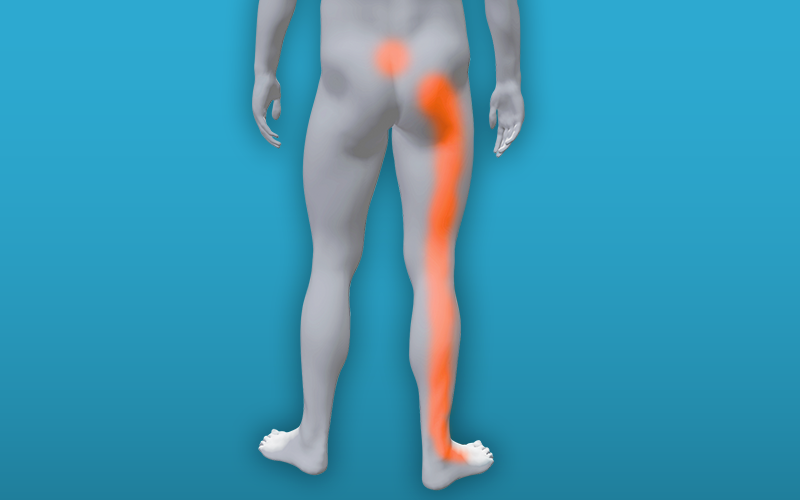

Leg pain – Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

What is Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS)* is a term used to describe pain in the legs caused by a problem in the lower back.

In the spine there is a central tunnel (canal) that protects the spinal cord as it travels from the neck to the lower back. By the time the spinal cord reaches the lower back it sends out several smaller nerves known as nerve roots. These continue to travel in the spinal tunnel of the lower back before they travel down into the legs. With age the spinal tunnel naturally matures, and this includes a gradual narrowing (stenosis) of the tunnel in most people. For some this narrowing can crowd (gently squeeze) and irritate the nerve roots.

*’Lumbar’ refers to the lower back. ‘Spinal’ refers to the spinal tunnel. ‘Stenosis’ means narrowing.

What are the symptoms of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

Common symptoms of LSS include an aching or cramping pain in the lower back, buttocks, thighs and/or calves. Symptoms vary from mild and intermittent to severe and disabling.

A hallmark feature of LSS is pain reproduced with standing and walking that is eased with sitting or with bending forwards (e.g., leaning forward on a shopping trolley). This is because the spine is flexed in these positions and the size of the tunnel increases. Other symptoms include heaviness or weakness in the legs with walking and cramps in the legs at night time. Some people with LSS may also experience pins and needles or tingling.

What causes Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

LSS is caused by spinal tunnel narrowing and irritation of the lumbar nerve roots.

The good news is that nerve roots are structurally resilient, and harm is unlikely to be caused when pain is felt. Pain can also be influenced by general factors such as reduced sleep, stress, and emotional wellbeing. Essentially anything that impacts general health.

An important message is that not all spinal tunnel narrowing will lead to symptoms. Narrowing of the spinal tunnel is a normal part of ageing. Approximately three quarters of people over the age of 40 are expected to have moderate spinal tunnel narrowing.

Who gets symptoms of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

LSS affects about 11% of the general population but it is very uncommon under the age of 50.

The average age is between 62 to 69 years old. Up to 60% of people with mild to moderate symptoms experience rapid improvement in symptoms or remain the same over time. Any progression of symptoms is usually slow. This allows time for symptoms to be monitored and for treatments to be considered.

Most people see their GP first who can usually make a clinical diagnosis based on what you tell them. The GP will be able to advise on first line management such as medication and exercise which is key to managing the condition. Depending on your symptoms you may be referred to a hospital specialist, who will assess and possibly request an MRI scan.

Are scans needed to diagnose Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Scans are not usually required to diagnose LSS.

LSS is a clinical diagnosis based on history, symptoms, and physical examination. For a group of people with severely limiting LSS, scan may be needed for surgical planning. Scans might also be needed when a serious medical disorder is suspected. Thankfully, these conditions are rare.

An assessment with your health professional will help determine if you require a scan.

Alternative causes of leg pain

Not all leg pain is related to LSS.

Pain sensitive muscles and joints of the back, hip and pelvis can cause leg pain. Another condition that may cause similar symptoms as LSS is Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) where the blood supply in the legs is restricted.

Your health professional can assess your problem to find out if you have LSS or whether your symptoms are caused by something else.

How is Lumbar Spinal Stenosis managed?

Management of LSS is based on several factors including symptom burden, general health, and treatment preference.

It’s safe for people to continue walking with leg pain as long as symptoms remain acceptable. For some, short pauses may be required. Bending the back when pain intensifies can also provide symptom relief (e.g., reaching to touch toes). Advice on lifestyle, weight loss and medicines review may be helpful but there is currently insufficient evidence to make any strong recommendations.

Whilst being supported to manage your problem, try to maintain things that bring value to your life. This might include things like playing with grandchildren, going for a meal with a friend or staying in work. This may be difficult at times, but it can help with coping and emotional wellbeing.

What is the prognosis of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis?

The outlook is unpredictable, but a general rule can be applied that with respect to symptoms:

- 1 in 5 will improve with time,

- 3 in 5 will stay the same,

- 1 in 5 will worsen with time. We have no way of predicting who will get worse.

How is Lumbar Spinal Stenosis treated?

The two treatment options for LSS are exercise therapy and surgical decompression.

The purpose of treatment is to alleviate symptoms and to improve quality of life. Treatment recommendations are based on clinical assessment, best available evidence, and patient preference. Current guidelines recommend an initial 12 weeks of progressive exercise therapy with or without support from a physiotherapist.

Discuss treatment options with your health professional.

Exercise as therapy

Exercise therapy is a first-line treatment for patients with LSS.

The purpose of exercise for LSS is not to change spinal tunnel narrowing but rather to reduce irritation and improve nerve root resiliency to movement. Exercise may also help with general function, muscle strength and balance associated with later life. Exercise is safe and offers several additional health benefits.

Examples of exercise therapy include a progressive cycling programme, an adjusted walking programme or stretching routine. For those with intense or disabling pain, exercise approaches that do not directly provoke pain like swimming may be suggested. Evidence for exercise therapy is inconclusive but studies are currently underway to better understand its role.

Please see below for further advice on exercises.

Surgical Decompression

Surgical management of LSS involves decompression of the nerve roots.

A procedure known as laminectomy where a small part of the spinal tunnel wall is removed. This may be considered if symptoms are severe, with progressive neurological decline or following a period of exercise therapy. There is currently no definitive evidence that laminectomy improves symptoms associated with LSS. While some have improvements in symptoms, others do not. Studies are currently underway to better understand the role of laminectomy in improving pain in patients with LSS. Injections are not usually recommended.

If laminectomy is considered your surgeon will discuss risks and benefits with you.

Exercises

Try these simple exercises to keep the back moving. Do these little and often through the day

Back Exercises will help keep your spine mobile and strengthen muscles. Ideally you should do these daily. These should include movements such as bending forward in sitting or standing whilst rounding your back. This movement can also be used for symptom relief, enabling you to continue with your chosen activity i.e., walking. Night pain and cramp can also be relieved by hugging one or both knees in towards your chest. Keeping the hips mobile is also beneficial.

Pacing refers to modifying activity levels to avoid the over/under active cycle through balancing activities throughout the day or week. Pacing means breaking your day into chunks of activity and rest, so that activities are spread out. It means not doing too much when you are feeling good or too little when you are not feeling so good.

Static cycling little and often to start with. Patients can often cycle with much less leg pain than when they walk. The use of an exercise bike can enable improvement in fitness and leg muscle tone. Start with just two or three minutes twice a day, and increase the time a little every few days.

Walking as tolerated. Walking up to symptom threshold then just a little further despite the pain will often improve walking distance over time. You may benefit from using a walking aid if appropriate.

General Strengthening If we have pain when doing physical activity, we tend to do less. Reduced activity deconditions us. This in turn can make our pain worse and so we do less activity, leading to a spiral of decline in function and walking. Progressive resistance training, using weights or body weight to improve muscle strength, may effectively reverse functional decline and improve functional outcomes in older adults. Such as repeated sit to stands (without using your hands), mini squats, mini lunges and using the stairs more often.

Balance exercises can enhance your walking and reduce your risk of falls. Such as standing in a semi tandem or tandem foot position (one foot in front of the other) with or without hand support. Reduced balance is linked to poor walking ability in patients with spinal stenosis.

Movement exercises

Bending in sitting

Relax and bend forwards enjoying the stretch on your back breathing slowly in and out a few times. Push through your legs to curl back up.

Repeat 5-10 times

Bending in standing

Relax and bend forwards enjoying the stretch on your back breathing slowly in and out a few times. Push through your legs to curl back up.

Repeat 5-10 times.

Back stretch

Lie on you back, either on a mat or your bed. Bend your knees, keep the back relaxed. Roll your knees from side to side.

Hold the stretch for 10 seconds and repeat 3 times on each side.

Pelvic tilt

Lie down with your knee bent. Tighten your stomach muscles, flattening your back against the floor (or bed)

Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 5 times.

Thigh stretch – One leg stand (front)

Holding onto support if needed, bend one leg up behind you. Feel a stretch in the front of the thigh.

Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 3 times on each side.

Knee to chest

Lie on your back, knees bent. Bring one knee up and pull it gently to your chest for 5 seconds.

Repeat up to 5 times.

Strengthening and balance exercises

Sit to stand exercise

Sitting in a chair, stand up and sit down slowly.

Try not to use your hands if possible.

Make this harder by:

- a) moving the foot of your affected knee closer to you and then progress to

- b) standing from a lower height.

Deep lunge

Kneel on one knee, the other foot in front. Facing forwards, lift the back knee up off the floor.

Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 3 times

Hip extension

Bring your leg backwards keeping your knee straight. Add an ankle weight as able, approx. 1-2 kg.

Repeat 10 times on each leg

Building up to between 1-3 sets each time

Further progressions would be to increase speed and weight.

Hip abduction

Lift your leg sideways and bring it back keeping your upper body straight throughout the exercise. Add an ankle weight as able, approx. 1-2 kg.

Repeat 10 times on each leg

Building up to between 1-3 sets each time

Further progressions would be to increase speed and weight.

Weight loss

If you are overweight then you may be advised regarding weight loss strategies.

Some patients may improve by the above measures. If any further intervention is indicated the above advice is still relevant as ensuring you are as fit as possible means that any further intervention would be safer and likely to result in a better outcome.

Simple painkillers

Painkillers like paracetamol will ease the pain, but need to be taken regularly in order to control the pain. Always follow the instructions on the packet.

Anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen can help with swelling, and therefore help you move more freely. Follow the instructions on the packet and discuss using them safely with a pharmacist, especially if you have any underlying health conditions

However, you should not take ibuprofen for 48 hours after an initial injury as it may slow down healing.

Up to date guidelines can be found on the NHS website:

Other medicines can help to reduce inflammation, swelling and pain. You should discuss this with your GP if the simple pain relief advice does not help or if you are needing to take ibuprofen for more than 10 days.

Some patients’ leg pain can lessen with appropriate medication. It may take a few months before it is clear if these simple measures are helpful. Remember it may hurt, but you won’t cause yourself harm!

Nerve pain control: In line with NICE guidance doctors can prescribe drugs to help reduce nerve pain e.g. Amitriptyline

If you are unsure and concerned about your symptoms, please see our ‘when to seek medical advice’ section on the back pain home page

Injections

If indicated spinal injections of steroid and local anaesthetic can also help some patients’ symptoms. They are helpful for leg pain rather than back pain.

These injections are usually requested by the hospital specialist.

Physiotherapy

Please contact your healthcare professional or refer yourself to physiotherapy for further advice and guidance.

Understanding the complexity of pain and other influencing factors

What we have learnt through research is that pain, especially persistent pain is more complex than just what is going on locally to where you feel the pain. It can be affected by many things including poor sleep, poor general health, reduced fitness, stress, past experience of pain and our beliefs about pain and our physical structure. The links below provide some insight into understanding pain, understanding your own beliefs around your pain and then looking at positive changes you can make that can in turn have a positive effect on your pain and levels of function.

Understanding pain in less than 5 minutes

Facts about back pain and exercise

10 things you need to know about your back

Abdominal breathing, relaxation and sleep

Stress and tension are common with persistent pain. For some it may be part of the underlying cause for many it’s a consequence as pain itself causes more stress and anxiety. What we know is that if we can use tools to help reduce our muscle tension and stress this can help with pain, sleep and function. Below are links you may find useful

Online video describing abdominal breathing

Breathe2relax. This is an APP specifically for abdominal/diaphragmatic breathing – go onto your smart phones APP store for more details

Understanding persistent pain – this booklet is commonly used by the Pain Management Service.